| Nikon D3 Digital Camera Reviewed |

|

|

| by Bj�rn

R�rslett |

|

9. D3

against the D300: FX vs DX format

Nikon has stubbornly endorsed

their "DX" format as the better approach to digital SLR

for a long time. They advocate the smaller-sized imager as being

the optimal solution for cameras compatible with existing 35 mm

cameras and lenses. Other companies, namely Canon and Kodak, have

pursued other avenues and designed "full-frame" (FF)

cameras. There is a wide-spread belief that "FF" is not

only desirable, but necessary to achieve top performance for

"35mm" DSLR models. With the entry of the new top

model, D3 and its FX format, time has finally come to make

qualified statements about the wisdom of Nikon's earlier DX-based

policy.

I chose to make the comparison

with D3 and D300, since they both are 12 MPix models. Intially I

thought of using the D2X as the alternative, but since a write-up

on the D300 is on my to-do list, I selected the latter model.

Admittedly, a fair comparison of these cameras is a tall order.

Fields of view are quite different of course, so are angular

resolution due to pixel pitches and pixel density. Amongst these

two, D3 has the biggest pixel pitch and the lowest pixel density,

D300 the opposite. The frame ratio aspects of the cameras are

slight different too, but close enough to 1:5:1 to have no

significance for my assessments.

Among the claims laid down in

favour of either format are finder size, sharpness,

depth-of-field (DOF) considerations, "reach" of longer

lenses, a "speed" advantage, vignetting behaviour,

noise performance, dynamic range, pricing, and size/weight. Since

a D2X/Xs (DX) is the same size and heft as the D3 (FX), we rule

out the latter directly. The inherent cost of the systems as they

now appear would appear to go in favour of the DX, but since

Nikon's FX is only just embarking its development this situation

could change in the near future. However, all things considered a

bigger sensor chip will always cost more than a smaller one. In

terms of noise, or rather, a better high-ISO performance, Nikon

has provided the answer by equipping D3 with 6400 ISO as the

highest calibrated setting plus giving boosted values up to 25600

ISO (equivalent), whilst the D2X/Xs went up to 800 ISO (3200 ISO

equivalent boosted), and the D300 is rated up to 3200 ISO (6400

ISO equivalent boosted). The recent crop of DX-format cameras

exemplified by the D300 has come a long way towards giving us a

better, bigger, and brighter, finder, but undeniably the D3 FX

has the upper hand in this department.

In terms of sharpness, pixel

density has to be factored into the equation. Thus, given that

the D300 has the (approx.) equal number of pixels as the D3, but

packed into the half area, it is obvious that D300 potentially

can record finer detail. Whether it does come out on top depends

on the subject, though. I've seen examples of either camera

delivering the "best" image under field testing

although the tendency is for the D300 to have the upper hand. But

since theory supports the notion that DX potentially can be

sharper than the (current models of) FX, I accept this as a fact

for now. However, in order to realise the better sharpness

potential, you need to be able to focus more accurately and this

requirement is not entirely compliant with the finders on these

systems.

Whether you consider the

cropped DX format to give more "reach" will depend

entirely on how you perceive and deal with

"magnification" of a framed shot. Using a 200 mm on a

DX camera gives smaller magnification than a 300 mm on an FX from

the same position and distance to the subject, but you get almost

identical field of view. So the same 300 mm lens now deployed on

the DX camera will actually increase detail magnification (to the

same level as on the FX, of course), but the field of view is

smaller. Many would argue this constitutes a

"magnificaton", which at best is a direct abuse of

terminology. What is happening is that you have effectively

cropped away more around the subject. You could equally well use

the FX camera and trim the image later, so as to achieve a

"DX crop" by indirect means (but the pixel density will

be lower since the pixel pitch remains the same).

The alleged "speed"

advantage is closely associated with the depth-of-field (DOF)

considerations. The reasoning goes as follows: According to

current DOF models, with DX you can use a lens with focal length

(DX/FX) at 1 stop larger setting and achieve the same DOF

extension as on FX. Thus, using a 200 mm lens at f/2 on DX will

result in the same DOF (and field of view) as a 300 mm lens at

f/2.8 with the FX camera, if both are shot with the same distance

to the subject. It's pretty obvious that the

"advantage" depends on which camp you consider yourself

being a member of. You could twist the argument and say that DX,

given that the assertion above holds, will allow you shorter

exposure times since you don't need to stop down to the same

degree. The entire claim also hinges on the (rather dubious)

assumption that the end user won't see a difference in how an FX

camera is used compared to a DX system. But for now, we just take

this assumption as a parameter to the sequence following.

Much of the debates that one

observes flare up on the Internet forums come from people heaping

upon their opponents arguments from DOF calculators. Now,

"DOF" is not a physical property, it is something

perceived and processed by the human mindset, and it is very much

an elusive quantity as well. Most DOF models are based upon

image-forming geometry, plus assumptions about the viewing

conditions to which the final image is subjected. All of these

parameters may be physically modelled with high precision yet

this tells nothing of the concordance between what is modelled

and what can be observed. Thus, typically the image won't clearly

break into "sharp" and "unsharp" areas with a

distinct border between them, rather there will be zones of

increasing sharpness (or unsharpness if you prefer going the

opposite direction). Where to draw a line and say

"inside" or "outside" a DOF zone is very

subjective. Digital images are essentially dimensionless until

they are outputted as something tangible, like a print hanging on

a wall. Thus, while we can envision the primary stage of optical

magnification, namely, the size of the details projected onto the

imager, it is more difficult to understand the r�le and amount

of secondary magnification (the enlargment stage that only can

make detail bigger, but not adding more information on its own).

Added complications are the pixel density and pixel pitch, which

both interact to limit spatial resolution of the captured image.

My first series of FX/DX DOF

comparison were conducted in the field using fairly long lenses,

such as 1200/800, 300/200, or 125/85, applied to landscapes.

While one might have an indication of differences, the actual DOF

for such shots is great enough to make the delineation of sharp

vs unsharp zones quite difficult, not to say a little

meaningless. I have posted some of these observations earlier and

the interested parties can consult them here.

In the FX/DX comparisons

following below, I tried to do a precisely defined setup that

could clarify differences FX/DX in more detail. I availed myself

of the fact that the 70-180 mm Zoom-Micro-Nikkor has its nominal

and effective aperture similar along its focusing scale. This

makes for elimination of potentially additional error since we

can use the same lens for either format and we are certain that

the apertures are compatible. I set up the test with a target

oriented precisely at 45� to the lens

and shot at a distance of 0.72 m with the Micro-Nikkor set to 122* mm and

180 mm for DX and FX formats, respectively.

*

although the EXIF reports 122 mm, I had the exact field of view

for both formats so the actual length should be very close to 120

mm. It seems the focal lengths reported by the 70-180 are not

continuous but have discrete steps, so one could either get 116

mm or 122 mm, but not 120 mm although the lens was set between

these two values.

First we test the basic

hypothesis that the format as such doesn't influence the depth of

field when the final magnifications give the same apparent size

of details. I have given supporting evidence for this earlier but

it doesn't hurt to repeat the test with a different experimental

layout.

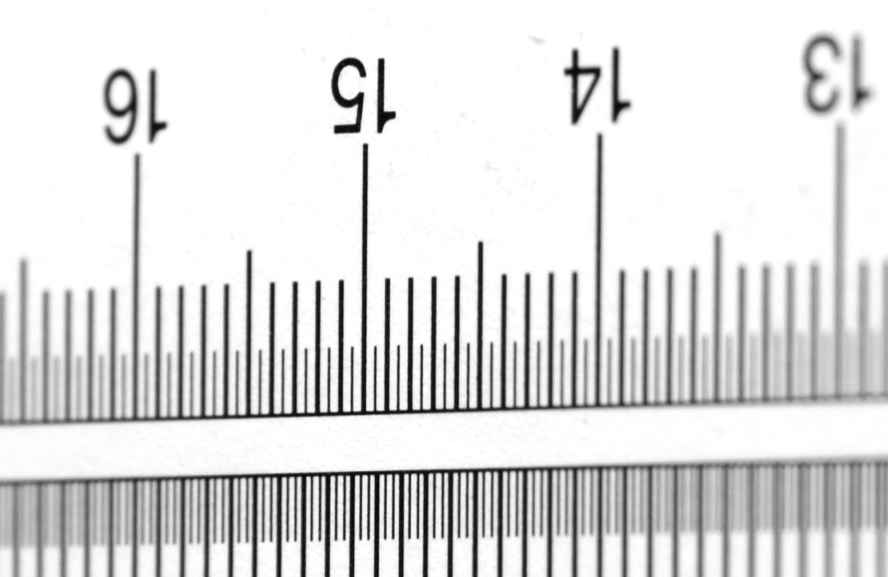

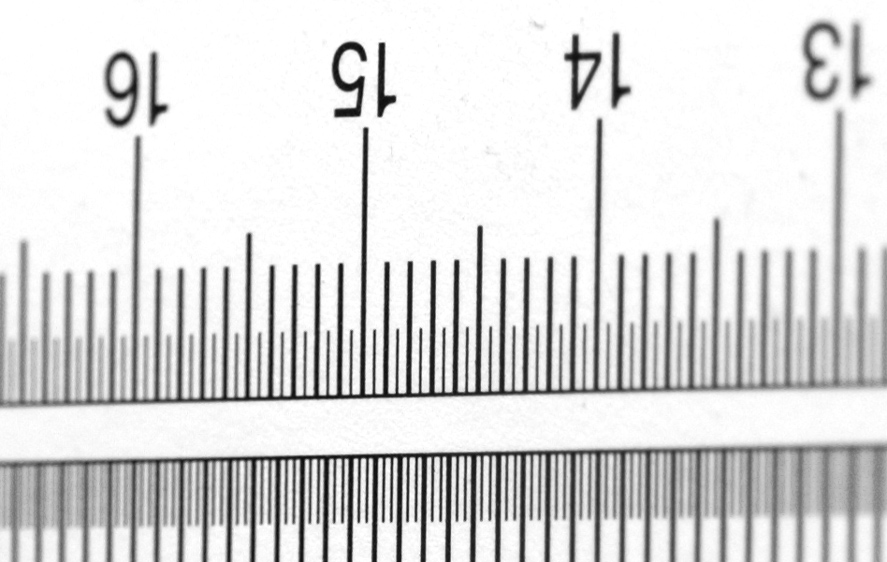

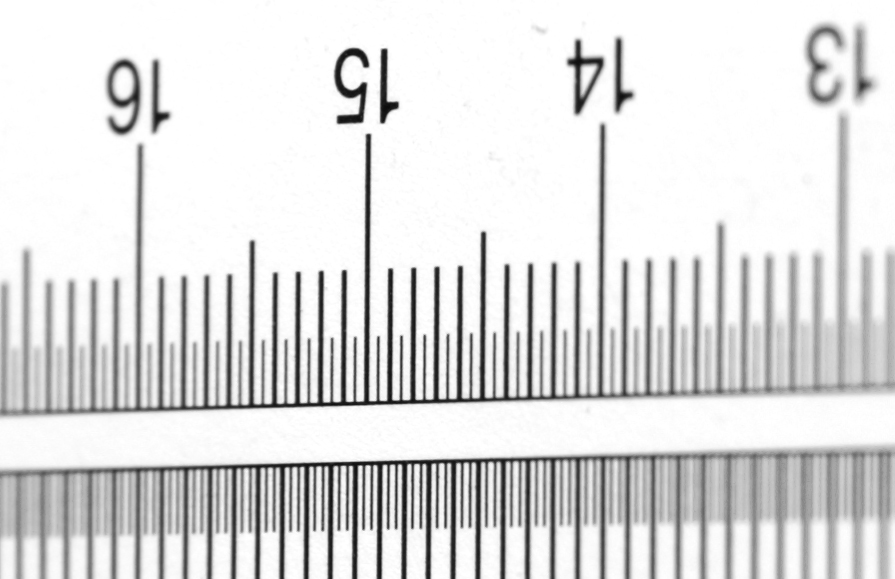

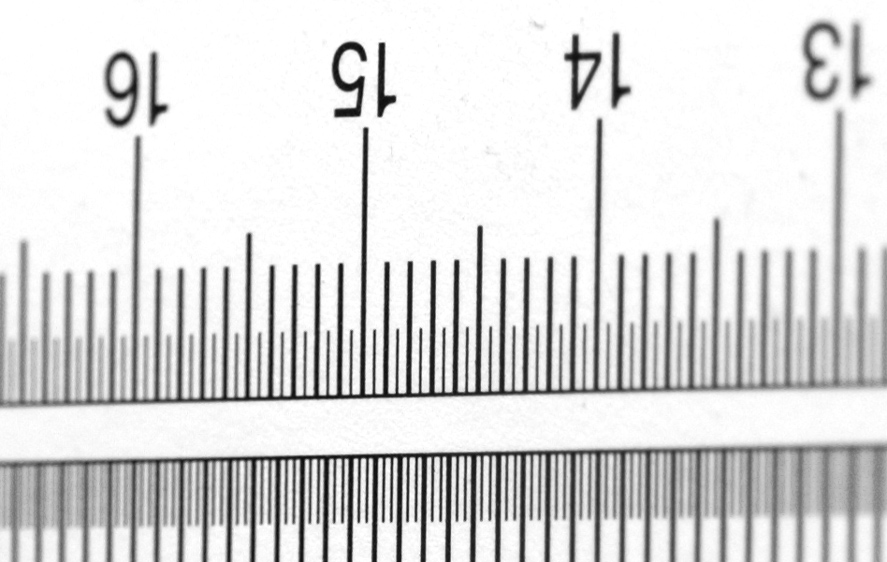

| Crop of the centre area of each

shot, scaled to match precisely the D3 image at 100%

(actual pixel size) or approx. equal a print of 36 x 54

cm (@200 dpi). The focused point is the "15" cm

bar, and all focusing was conducted using LiveView at

maximum magnification. Flash (SB-800) used for lighting

the subject. NEF files processed in BibblePro 4.9.9b at

default settings and the crops of the TIF files from

Bibble converted to jpg in Photoshop |

Description of crop

(f=focal length, N=f-number, m=magnification) |

|

Reference

D3, FX frame

f = 180 mm,

N= 8,

m=0.2

Upper scale is in cm and has 45�

inclination to the optical axis. Thus, multiply any DOF

estimate read from this scale by 0.7 to get the

along-axis value

|

|

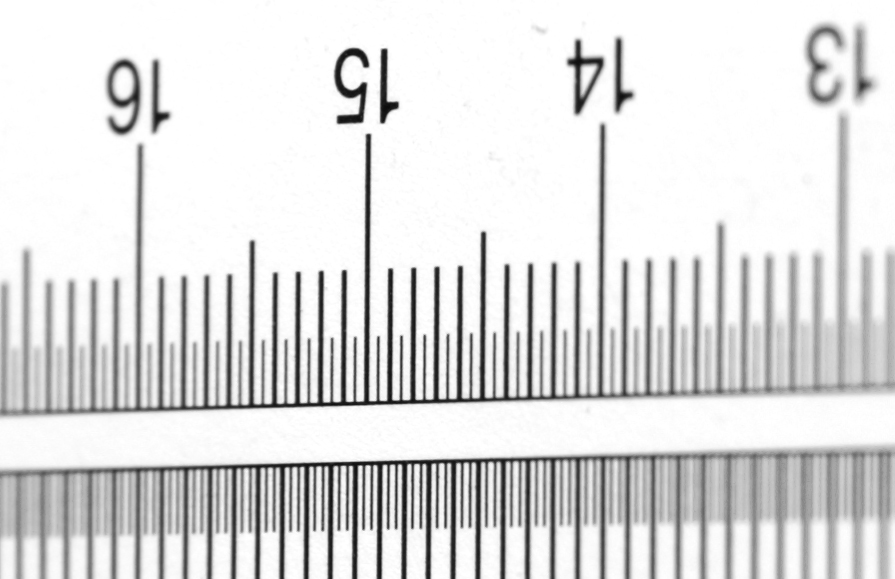

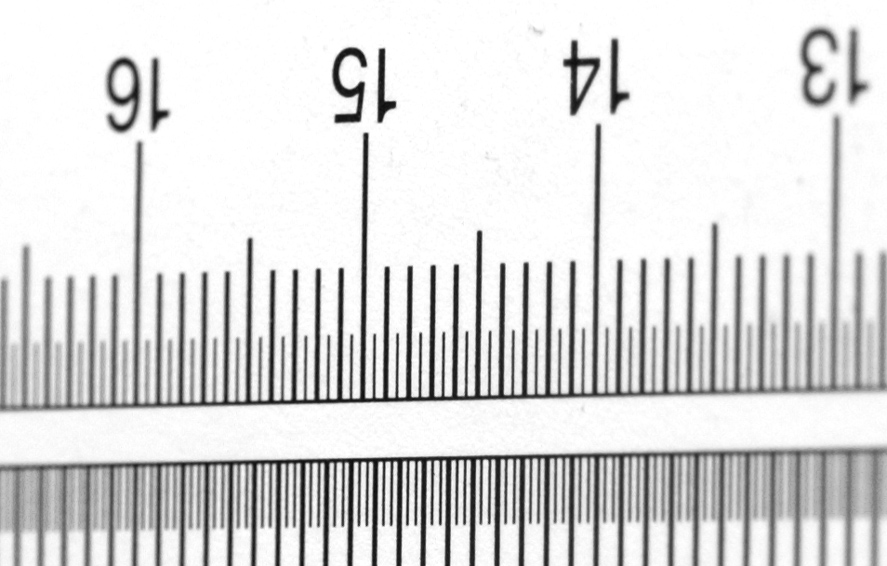

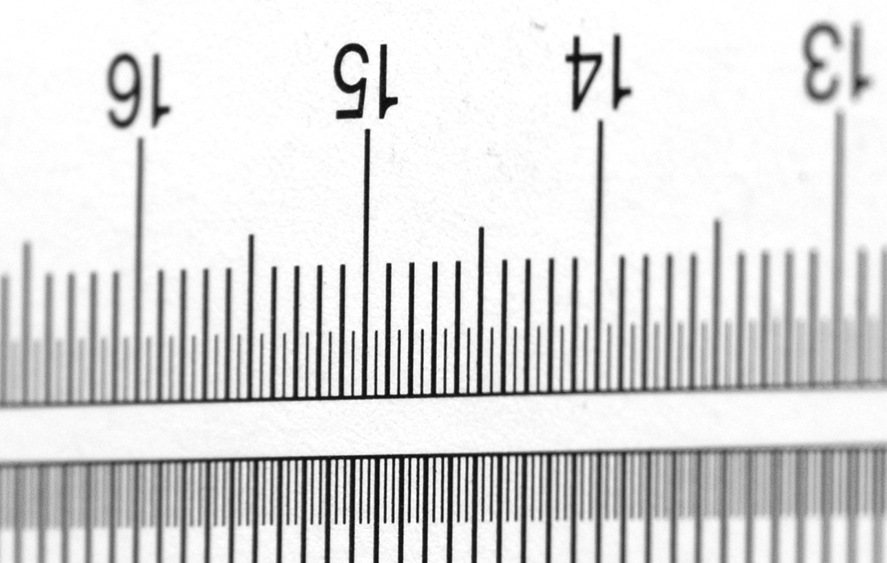

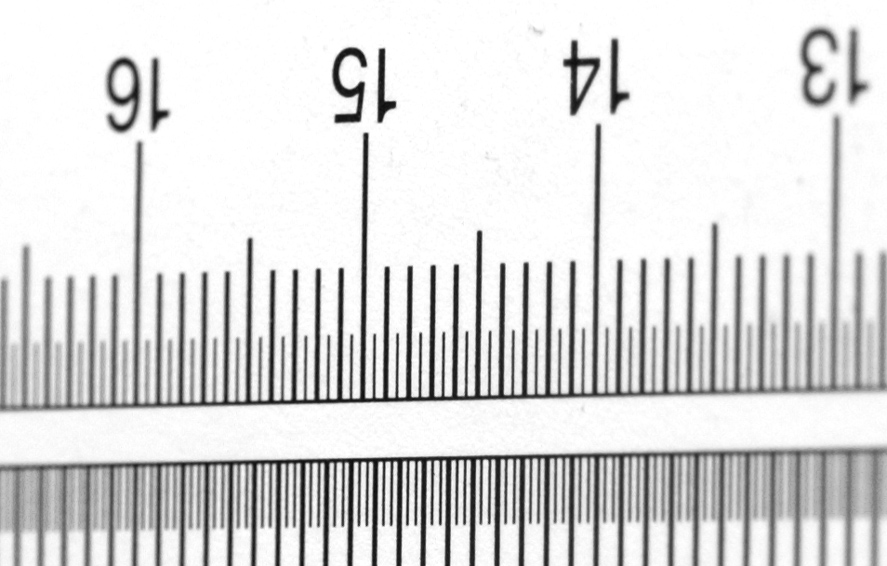

D3,

DX frame f=180 mm,

N=8,

m=0.2

|

|

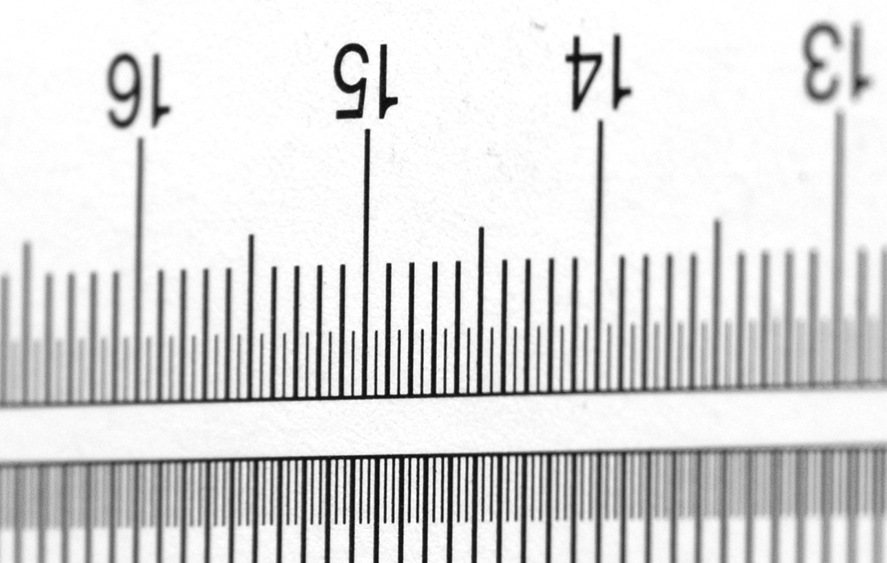

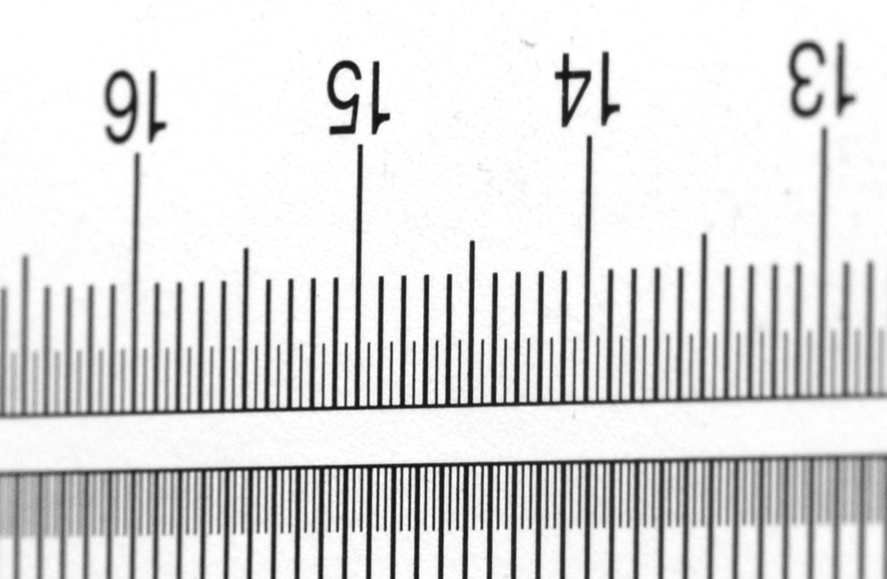

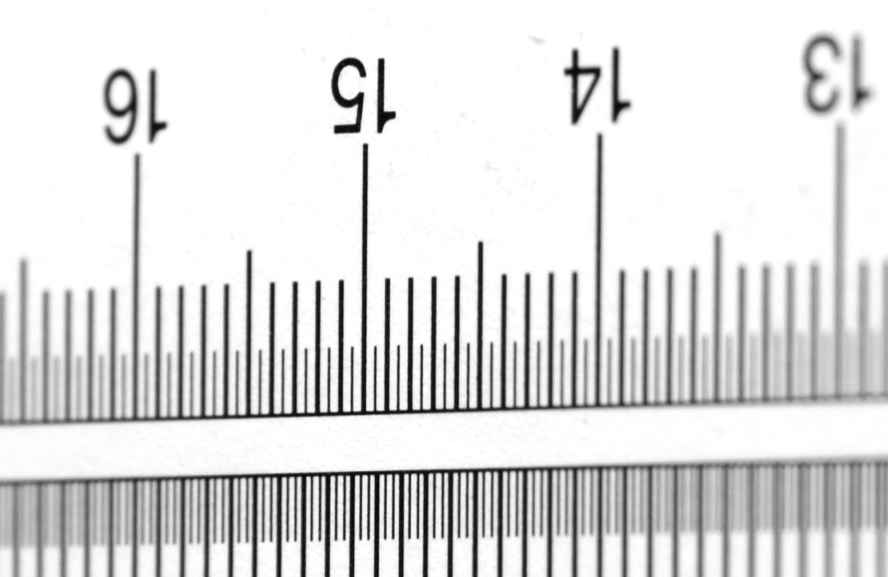

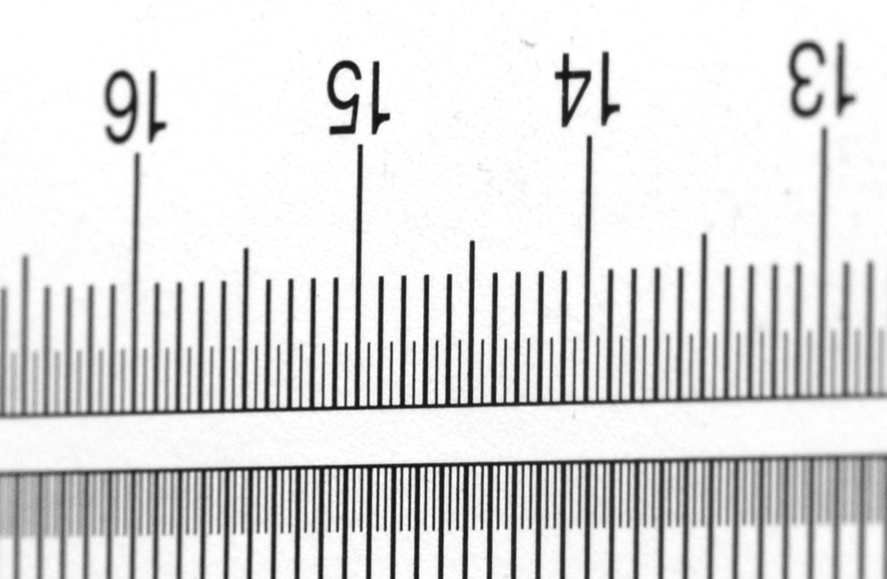

D300, DX frame

f=180mm,

N=8,

m=0.2

|

Does this comparison corroborate that using

the smaller "DX" format in itself will impact the depth

of field, a claim that so frequently is encountered? Honestly I

don't think so. Within the error of the experimental setup, all

crops appear to be identical in terms of their distribution of

detail sharpness. What we can observe, albeit just barely, is

that the lower pixel density (but identical pixel pitch) of the

DX mode of the D3 renders the final image just a tad less crisp

when it is brought to the same apparent size as the others.

In the case above, the primary

magnification (concerning detail at the film plane) is kept

similar. Now, we venture into the dire straits favoured by the

"equal FOV" fans. This is to say that you deliberately

put the smaller format at an disadvantage in order to make the

captured field of view identical. In this process, if we choose

to keep perspective equal, then picture angles will be different

and so will detail magnification by a factor of the ratio of

FX/DX diagonal (1.5 in this case). You could offset this drawback

by being able to open up 1 stop more so as to give a shorter

exposure time. All again per the parameter set I outlined

earlier. Now, let's check how reality fares against the

predictions.

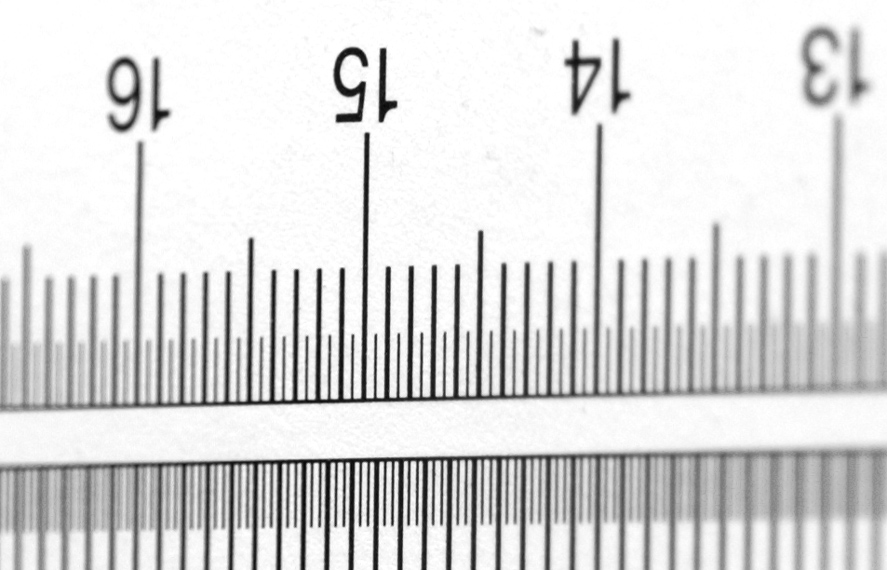

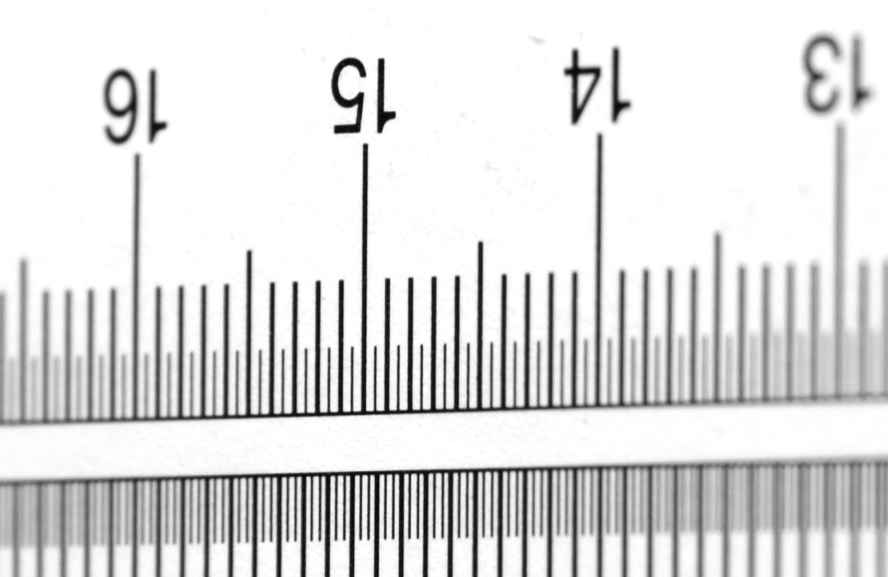

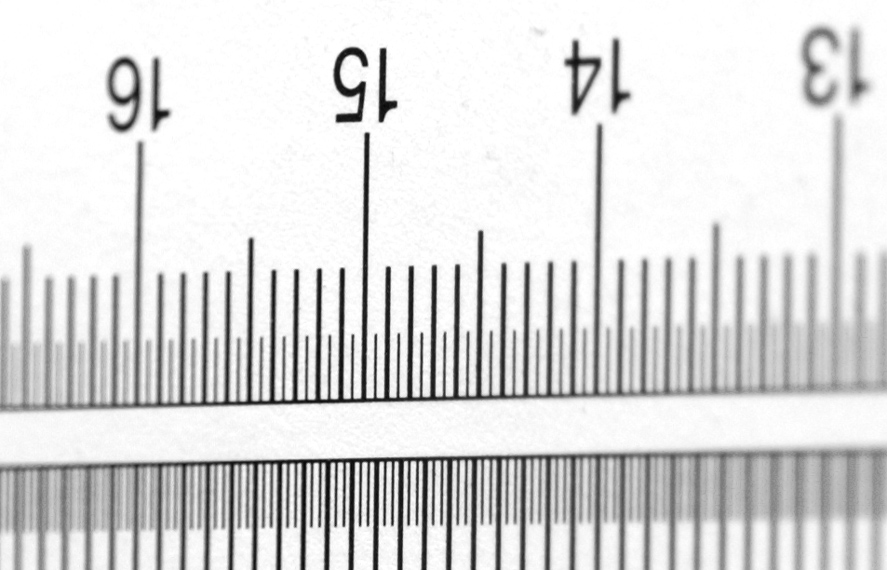

| Crop of the centre area of each

shot, scaled to match precisely the D3 image at 100%

(actual pixel size). The focused point is the

"15" cm bar, and all focusing was conducted

using LiveView at maximum magnification. Flash (SB-800)

used for lighting the subject. NEF files processed in

BibblePro 4.9.9b at default settings and the crops of the

TIF files from Bibble converted to jpg in Photoshop. Note

that now we allow detail magnification to vary so as to

give the same field of view, but at different focal

lengths |

Description of shown crops |

|

Reference

D3, FX frame

f = 180 mm,

N= 8,

m=0.2

Upper scale is in cm and has 45�

inclination to the optical axis. Thus, multiply any DOF

estimate read from this scale by 0.7 to get the actual

value

|

|

D300,

DX frame f=122 mm,

N=5.6,

m=0.13

|

|

D300, DX frame

f=122mm,

N=6.3,

m=0.13

|

|

D300, DX frame

f=122mm,

N=7.1,

m=0.13

|

|

D300, DX frame

f=122mm,

N=8,

m=0.13

|

What can be learned from the panel above is

the stark real-life existence and behaviour of the

"DOF" issue. There is no such thing as "real"

phenomena which can be measured and plugged into a nice,

quantitative model. Essentially, perceived DOF is a qualitative

variate. We can compare the manifestations of it in a given

picture under a set of viewing conditions and say

"more" or "less, but not "twice as much"

or "half the amount". This is the data to debate and not the output from a

DOF model.

The visual differences obviously are small,

almost down to the nit-picking level. So even a full stop

variation of the aperture setting gives negligible changes in the

perceived DOF. Feel free to quantify the "speed"

advantage of the DX format here. Is it one stop as claimed? Or is

the better question rather: does the format matter? Or are we

back to an apples vs oranges discussion again? I leave the

decision to the reader. If you perceive the matter differently,

just fine with me, we're talking about subjective impressions

here.

So, what about the FX vs DX statement

presented in the opening of this page. Nikon has ruled in favour

of supporting both formats for the foreseeable future. As of now,

if you wish to have the smaller, most portable camera, with an

image quality capable of surpassing the D3 in resolving power,

well, then the D300 is the answer. If you need the utmost

ruggedness, the extreme high-ISO performance, or the ultimate

firing rates, well, then the D3 is the better option. Or if you

do close-up work and just demand the best finder, again the D3

comes to mind. If you are into wildlife photography, a D2X or a

D300 might be a "better" camera" than the D3

unless you also have to have the ultimate high-ISO performance

and call upon the D3. For close-up work, being in position to use

longer lenses is a plus for D3 and having the better finder handy

won't hurt either. And so on, ad nauseam.

The list of pros and cons for these two

formats is literally endless. You simply have to define your

requirements and find the format and camera model that slots in

the best. From this point of view, the dual support of FX and DX

format is a very wise move.